December 31, 2018

Netflix’s Interactive Movie Black Mirror: Bandersnatch - Great Concept, Limiting Execution

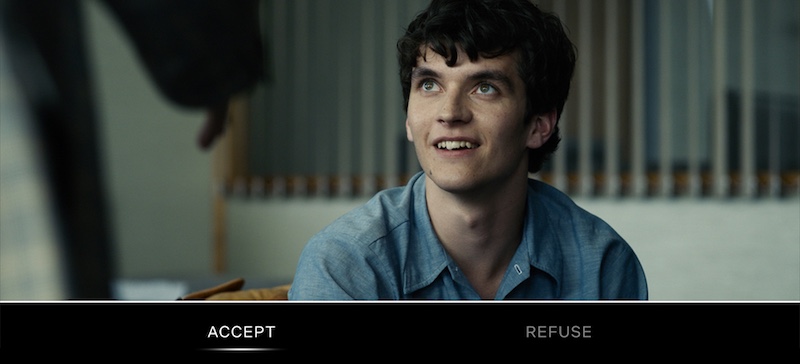

The talk of the town during the weeks leading up to the beginning of the 2019 new year was the new interactive movie on Netflix, Black Mirror: Bandersnatch. This film was Netflix’s first major venture into interactive movies where as a viewer you get to make choices at specific moments in the film and influence the plot and final outcome. While I completely grasp the concept of an interactive film and the enjoyable possibilities presented, in this case the movie was just too dull and dry for me to actually enjoy the nuances delivered with this new form of media engagement.

The idea of interactive movies is referred to as “interactive cinema.” It is a concept that dates back to 1967 where the first interactive film, Kinoautomat by Radúz Činčera, gave viewers nine moments throughout the movie where the audience got to choose which of two scenes would be played next. Over the decades since that time interactive cinema has taken on many forms and gained a wider adoption, especially in the gaming industry. It was a key gameplay element during the rise of LaserDisc interactive games back in the early 1980s. The bulk of LaserDisc games centered around playback of pre-recorded video clips based on a user’s input. One of the most notable and popular examples of an interactive cinema LaserDisc game is the all-time classic Dragon’s Lair, which was released in 1983.

So interactive cinema isn’t a new concept. Yet Netflix’s fray into this genre gives it a global audience and places the genre center-stage for the entire world to experience. I, personally, was extremely excited when I first heard about this new type of entertainment. Based on the viewer’s selections you supposedly would be able to lead the movie to completely different endings. Wildly curious was I. How were scene choices presented to the user? What happens if you don’t make a selection? How much time were you allotted to choose? Would my deliberations interrupt the pace of the movie? So many questions, so much intrigue.

… interactive cinemas could become a very engrossing and engaging form of entertainment. One where we struggle to understand how we ever lived without it.

After seeing the final product, I must say I was convincingly impressed. The delivery, the simplicity of how the choices were presented to the user, the ease of making a selection, it all fits and makes sense. The timing given for next scene selection was spot-on and flowed nicely with the film. The first three or four selections felt great and gave me this sense of being in control of the storyline. I was fully engaged in how my movie would turn out. Yes… “my”. I suddenly was endowed with a sense that this film was now unique to me and the choices I make. That’s around the time reality started to set in and I realized the film, itself… just didn’t measure up.

The movie’s plot was so dry and boring that it struggled to maintain my attention. There barely was enough visual activity and dialog most of the time to keep my interest long enough to even notice when a choice was on screen awaiting my response. What’s worse is that the interactive portions of the movie often didn’t lead you anywhere. When you didn’t select the proper or expected outcome, you were forced to go back and redo the previous scene selection. I really wished there were more choices that offered a completely different pathway through the movie because what everyone truly wants is the option to become either the hero or the villain.

This first mainstream version of interactive cinema, in my opinion, was just too limiting. It appeared that in moments where a user choice seemed obvious, no choice was offered. The film had a very rigid set of endings that forced viewers to follow a specific choice path. I clearly see the need for a restriction in the number of choices presented, as there’s only a finite amount of footage available for the film. However, my wish is that when your choices lead onto a branch that does not flow into one of the defined endings, that scenario should handled gracefully and still feel in unison with the film. That versus the abrupt “Go Back” selection screen actually presented in those situations.

This may sound really harsh, but once I finally reached an ending and the credits rolled; I felt relieved. It was just so dull and boring of a movie that I have never been so delighted it was over. Some may find my critique off-base, while others may praise the movie for the depth of its characters or its hidden symbolism and technical references. However, if you ask my opinion, the film truly struggled to maintain a viewer’s interest. In the end, I verbally uttered the words, “please… no more. I’m done.”

… I highly recommend everyone to experience this movie for themselves.

The genre itself works. While this highly broadcast outing into interactive cinema was just too gimmicky, as a first iteration my curiosity is definitely stoked about the possibilities that lay on the horizon. Given more options, a better storyline — much, much better storyline — interactive cinemas could become a very engrossing and engaging form of entertainment. One where we struggle to understand how we ever lived without it. Despite my critique, I highly recommend everyone to experience this movie for themselves.

This first film solidly proved viewers would watch as well as participate throughout the movie. The ratings cited nearly 26 million U.S. viewers watched and participated in this movie during its first week alone.

Interactive cinema works. Viewers will participate. This first movie was an introductory offer, but it’s got me excited and eager to know what future installments have to offer.